In the second part of this series on Gulf of Mexico (GoM) well activity, trends for exploration and development wells are described.

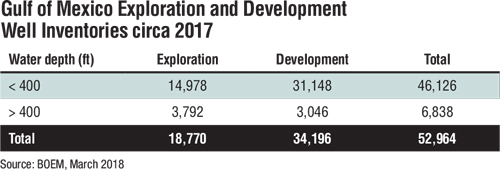

The purpose of exploration is to find commercial quantities of oil and gas, and wells drilled to produce known reserves are classified as development wells. From 1947-2017, there were 14,978 exploration wells drilled in the GoM in water depth less than 400 ft (122 m) and 3,792 exploration wells drilled in deepwater. A total of 31,148 development wells have been drilled in shallow water and 3,046 deepwater development wells have spudded circa 2017.

An exploration well is drilled outside known reservoirs, and therefore, operations almost always take place from a mobile offshore drilling unit. In water depth less than 500 ft (152 m), jackups are used exclusively for drilling exploration wells; in deeper water, semisubmersibles and drillships are required.

Exploration is part of an oil and gas company’s discretionary spending and activity fluctuates annually with changes in oil and gas prices, discoveries, geologic prospectivity, company budgets, new technology, and many other factors.

Excluding side tracks, shallow and deepwater exploration well counts totaled 12,895 and 2,549 wells, respectively, meaning that about 16% of shallow-water exploratory wells compared to nearly half of all deepwater exploratory wells are side tracked. These differences are due in large part to differences in the cost and complexity of drilling in the two water depth regions. In deepwater, complex geology and expensive wells requires operators to extract the maximum amount of information from the drilling campaign, which frequently entails side tracking wells even if they turn out to be dry holes.

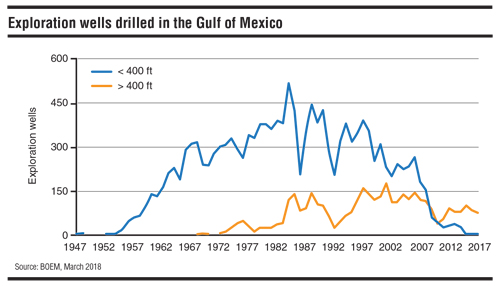

From the early 1960s through 2006, at least 200 shallow-water exploration wells were drilled annually, and in many years activity levels were twice as high. Exploration activity peaked in the mid-1980s between 400 and 500 wells per year. High levels of volatility characterize activity during this period.

Since 2006 exploration well counts have been in steep decline. In 2008, 153 exploration wells were drilled followed by 60 wells in 2009 and less than 50 wells per year thereafter. A total of nine exploration wells were drilled from 2015-2017.

Deepwater drilling has never exceeded 200 wells per year and over the past two decades have ranged between 50 and 150 wells per year. The number of deepwater exploration wells drilled have fluctuated within a narrower range than shallow water, hitting a low in 2010, the year of the Macondo oil spill and the deepwater drilling moratorium, before bouncing back. From 2015-2017, 260 deepwater exploration wells were drilled.

Exploration activity in shallow water has dropped significantly due to a combination of factors, including lack of new discoveries, sustained low oil and gas prices, and the growth and success of onshore shale plays, especially unconventional shale gas. The lack of new discoveries arises from the maturity of the region and past development.

Shallow waters in the Western and Central GoM have been extensively explored and the probability of major new (large) discoveries in the region are considered low. Oil prospects continue to attract attention in and around existing oil fields and deeper in the Miocene, but success rates and commercial finds over the last several decades have not been significant.

There has been no significant new plays or prospects announced by operators in shallow water in several years, and previous excitement for deep gas (e.g., Davy Jones, Blackbeard) has not materialized because of high-cost complicated wells and disappointing production. Fortunately, deepwater exploration continues to attract significant attention and capital spending because of new discoveries and high regional prospectivity.

The number of wells required in field development depends upon the size and complexity and depth of the reservoir sands, number of fault blocks, desired production rates, well type, development strategies, and other factors.

The majority of development wells are usually drilled during the early stages of field development in the traditional spend-produce business model. However, development drilling will also occur throughout a field’s life as producing zones are plugged back and side tracks drilled or additional phases of development occur. Phased developments are often the preferred strategy for complex reservoirs or where the operator wants to limit initial development costs.

Circa 2017, a total of 31,148 shallow-water and 3,046 deepwater development wells with side tracks were spud. Excluding side tracks, well counts total 23,208 shallow-water and 1,654 deepwater development wells.

About one-third of shallow-water development wells and more than 80% of deepwater development wells are side tracked, about twice the percentages observed in shallow water. The increase in side tracking in development is not surprising, since after a well is drilled the opportunity to seek additional pockets of reserves at a reduced cost is often a favorable business decision.

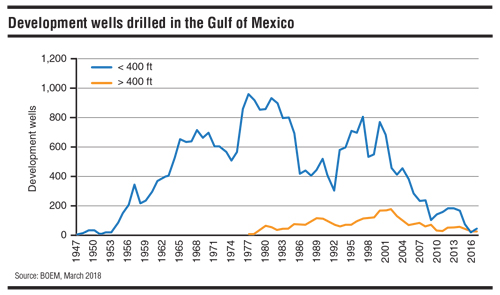

Development drilling follows successful exploration activity and in shallow water peaked in the mid-1970s and then peaked again at lower levels in the late 1990s.

From the mid-1960s through 2004, shallow-water development well counts ranged between 400 and 1,000 wells per year with smaller levels of activity from 1986 through 1992 due in part to depressed oil prices during the period.

In 1978, production began from the deepwater Bourbon and Cognac fields, about a decade after the first exploration wells were drilled in the region.

The number of development wells in shallow water are about twice the exploration inventories, whereas in deepwater development wells (currently) fall below exploration totals. There are several reasons for these differences. First, successful deepwater exploration wells may be completed as producers more frequently than in shallow water. Second, wet wells are commonly employed in deepwater development and are usually not side tracked to the extent that dry tree wells are side tracked, contributing to smaller well counts. Third, deepwater reservoirs usually have higher pressures and flow rate potential than shallow-water reservoirs, and less wells will be needed in development. Capital constraints associated with deepwater development will also limit the number of wellbores allowed.

Trends in shallow-water development drilling reflect the production decline in the region, and since 2008 less than 200 development wells per year have been drilled.

The number of deepwater development wells has also declined during this period, but deepwater oil production, after production upsets arising from the 2008 hurricane season, has increased.

In 2000, there were 772 shallow-water and 168 deepwater development wells drilled. In 2017, 43 shallow-water and 26 deepwater development wells were drilled. From 2000-2017, 4,995 shallow-water and 1,414 deepwater development wells were drilled. •